“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” – William Shakespeare

What if I told you that life is nothing more than a vast, intricate game?

Not in the trivial sense of leisure and amusement, but in the fundamental reality that every choice we make is a move in a larger strategy. From the way we interact in relationships to how nations engage in global politics, we are all players in an endless series of interconnected games, where every decision influences the outcomes of those around us.

Welcome to game theory, the mathematical and philosophical study of strategic decision-making. It doesn’t just apply to chess or poker; it governs everything from business negotiations to social trust, from economic markets to environmental sustainability.

To understand life through this lens, we must explore the four fundamental dilemmas of game theory—each revealing deep truths about human behavior—and the winning strategies that allow us to navigate them wisely.

Life as a Collection of Games

At every moment, we are making choices within an invisible matrix of strategic interactions. Do you cooperate or compete? Do you trust or betray? Do you consume or conserve? These are not isolated incidents but recurring themes, echoing in different forms across time and context.

When you and a friend decide who will pay for coffee, you're playing a game.

When a business sets its prices in response to competitors, it’s engaged in a game.

When you choose whether to hold the elevator for a stranger, you’re making a strategic move in a silent social contract.

Understanding game theory is not just about mathematical models—it is about understanding ourselves.

Let’s explore the four fundamental dilemmas of life’s grand game.

1. The Prisoner’s Dilemma: The Eternal Conflict of Trust

In its simplest form, the Prisoner’s Dilemma presents two individuals facing a choice: to cooperate or to betray. If both cooperate, they both benefit. But if one betrays while the other trusts, the betrayer wins big while the other suffers. If both betray, both suffer—just not as much as the one who gets exploited.

This is the paradox of trust: in the short term, betrayal often appears to be the logical choice, yet in the long term, it leads to widespread dysfunction.

Winning Strategy: Tit-for-Tat

The best response? Tit-for-Tat—a strategy of reciprocity. Start by cooperating, but if betrayed, respond in kind. This ensures that trust is rewarded while exploitation is punished. It is the foundation of long-term relationships, business partnerships, and global diplomacy.

Here is a detailed flowchart for the Prisoner’s Dilemma, illustrating the possible decisions and their consequences:

Scenario:

Two individuals are arrested and interrogated separately.

Each prisoner must choose to stay silent or confess.

Outcomes:

Both Stay Silent: Each gets 1 year (best mutual outcome).

One Confesses, One Stays Silent: The confessor goes free, while the silent one gets 3 years.

Both Confess: Both get 2 years (worse than mutual silence, but better than being betrayed alone).

This visual breakdown clarifies why betrayal is tempting, even though cooperation leads to the best collective outcome.

🔹 Lesson for Life: Trust, but verify. Forgive, but never forget.

2. Nash Equilibrium: The Unstable Stability of Life

The Nash Equilibrium, named after mathematician John Nash, is the state where no player can improve their situation by changing their strategy alone. It is a balance—though often an imperfect one—where everyone is locked into choices that, while stable, may not be ideal.

Consider two rival coffee shops on the same street. If one lowers prices, the other must follow. If one raises them, customers flock to the competitor. Eventually, both settle on a price where neither benefits from changing alone.

This is the dilemma of competition: we may find ourselves trapped in behaviors that are not optimal, yet no one dares to deviate.

Winning Strategy: Coordination and Randomization

In some games, the best strategy is to establish focal points—natural agreements or norms that create order (e.g., everyone driving on the same side of the road).

In competitive games, randomization prevents predictability (e.g., mixing up pricing strategies or military tactics to remain unpredictable).

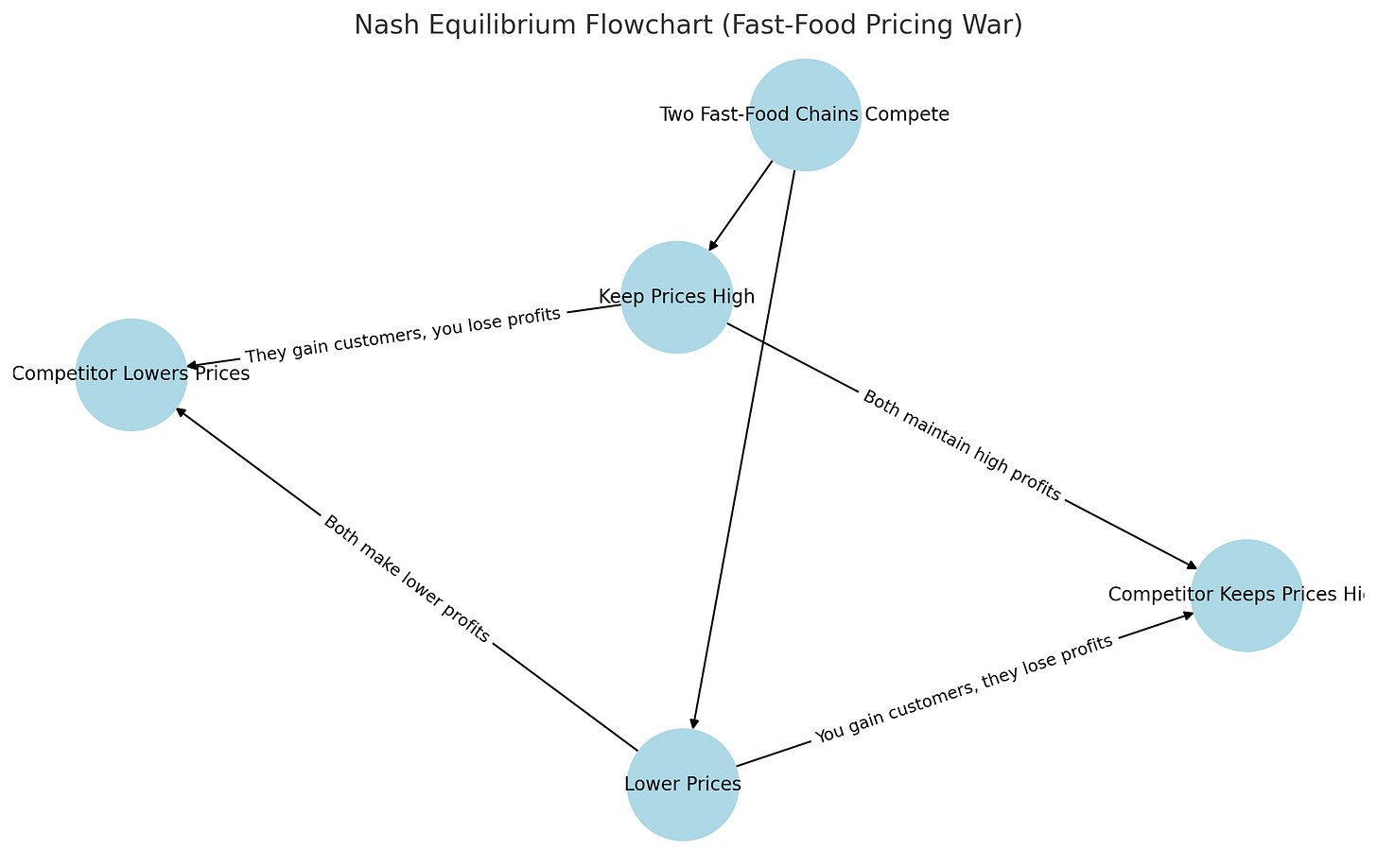

Here is a detailed flowchart for the Nash Equilibrium, using the real-world example of a Fast-Food Pricing War:

Scenario:

Two fast-food chains compete in the same market.

Each company must decide whether to lower prices or keep prices high.

Outcomes:

Both Lower Prices: They attract more customers but make lower profits.

One Lowers, One Keeps Prices High: The one who lowers gains customers, while the other loses profits.

Both Keep Prices High: They both maintain high profits—this is the Nash Equilibrium, since neither benefits by changing their strategy alone.

This visual representation helps explain why business competitors often get stuck in a price war or find stable pricing strategies that neither wants to deviate from.

🔹 Lesson for Life: Recognize when you are in an unwinnable situation and seek to change the game itself.

3. The Tragedy of the Commons: The Greed That Devours

The Tragedy of the Commons is the story of human selfishness writ large. Given access to a shared resource—whether it be fish in the ocean, trees in a forest, or even clean air—individuals have an incentive to take more than their fair share. If everyone does so, the resource collapses, and all suffer.

Why does this happen? Because the cost of restraint is individual, while the cost of overconsumption is collective—until it’s too late.

Winning Strategy: Incentives and Enforcement

Regulations (e.g., fishing quotas) and economic incentives (e.g., carbon taxes) align individual behavior with collective well-being.

Social norms and reputation also play a crucial role; when communities self-police, overuse is discouraged.

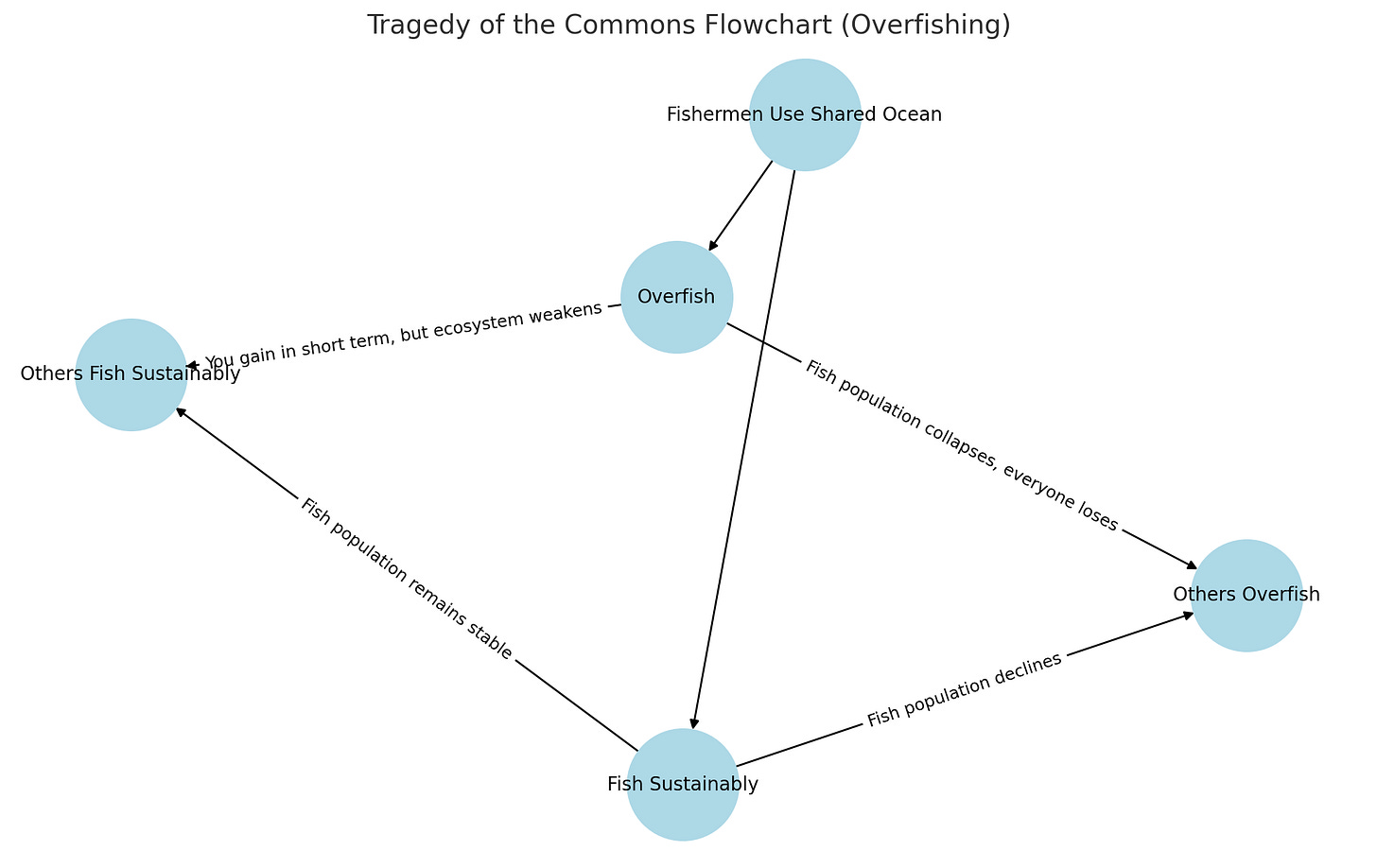

Here is a detailed flowchart for the Tragedy of the Commons, using the real-world example of Overfishing:

Scenario:

Multiple fishermen share an ocean as a common resource.

Each fisherman must decide whether to fish sustainably or overfish for immediate profit.

Outcomes:

Everyone Fishes Sustainably: The fish population remains stable, allowing for long-term benefits.

You Fish Sustainably, Others Overfish: The fish population declines, making future fishing harder.

You Overfish, Others Fish Sustainably: You gain in the short term, but the ecosystem weakens.

Everyone Overfishes: The fish population collapses, and everyone loses.

This visually demonstrates how individual incentives lead to collective disaster when shared resources are exploited without regulation or cooperation.

🔹 Lesson for Life: The best way to protect a shared resource is to make sustainability rewarding, and overuse costly.

4. The Stag Hunt: The Fragility of Trust

In the Stag Hunt, two hunters must choose whether to hunt a stag together (a big reward requiring cooperation) or hunt rabbits alone (a smaller but guaranteed reward). If one defects to hunt a rabbit, the other loses the chance at the stag.

This game reflects the risk of cooperation: The best outcome requires trust, but the fear of betrayal tempts players to settle for less.

Imagine two entrepreneurs considering a partnership. If both commit fully, they could build something great. But if one backs out, the other suffers.

Winning Strategy: Reputation and Small-Scale Trust-Building

Start small—build cooperation gradually before committing fully.

Establish a reputation—trust grows when it is consistently rewarded.

Use enforceable agreements—contracts, treaties, or public commitments reduce uncertainty.

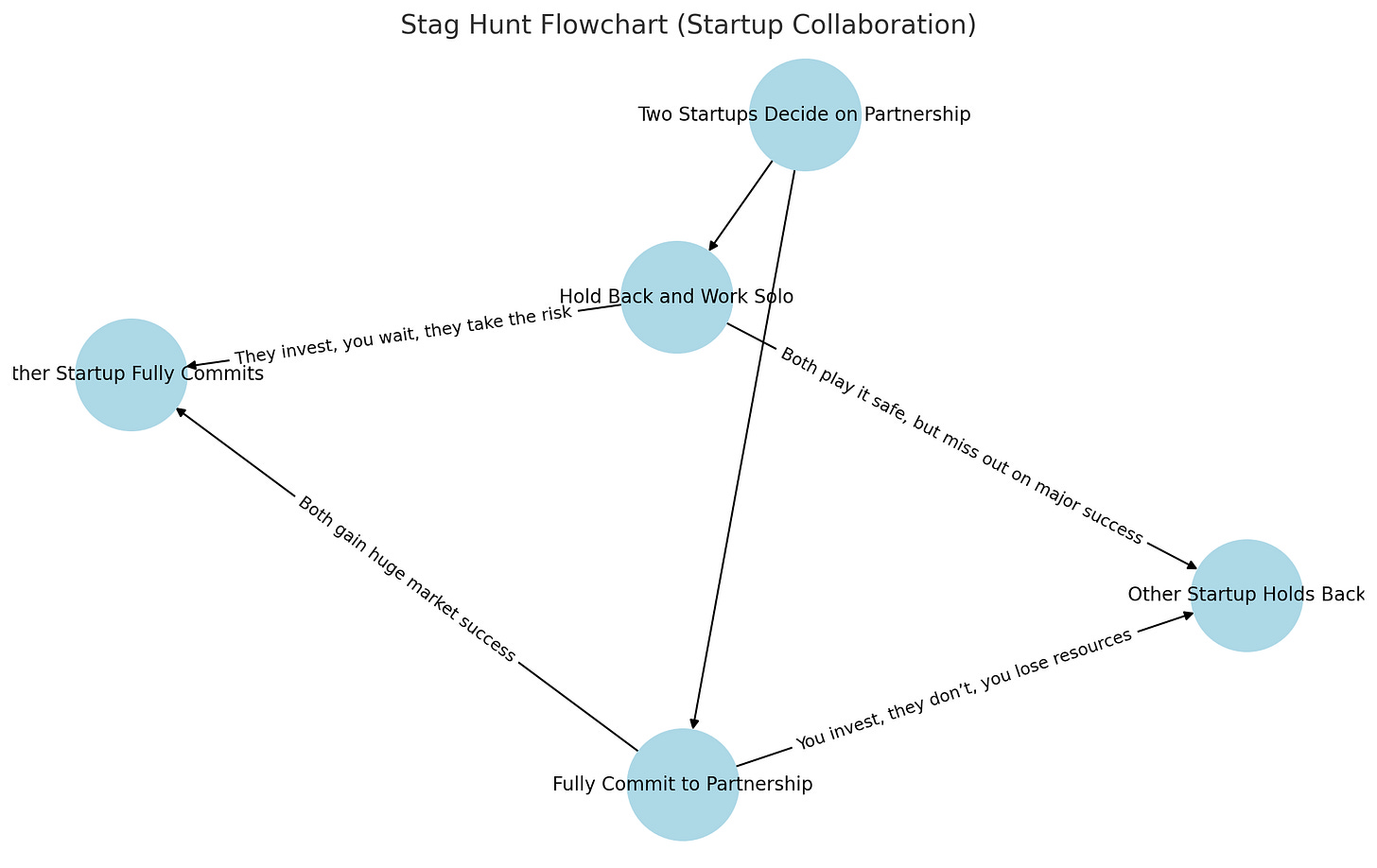

Here is a detailed flowchart for the Stag Hunt dilemma, using the real-world example of Startup Collaboration:

Scenario:

Two startups consider forming a strategic partnership.

Each startup must decide whether to fully commit to the partnership or hold back and work solo.

Outcomes:

Both Fully Commit: They achieve huge market success together.

One Fully Commits, the Other Holds Back: The committed startup invests resources and risks failure, while the cautious startup avoids risk but doesn’t reap full rewards.

Both Hold Back: Neither takes the leap, and while they avoid risk, they miss out on major success.

This visually explains why trust and mutual commitment are essential in business partnerships, alliances, and collaborative ventures.

🔹 Lesson for Life: The best opportunities require trust. Build it, don’t waste it.

Final Thought: The Meta-Game of Life

We live in a world of millions of interconnected games, playing out in relationships, businesses, communities, and nations. Every choice—big or small—is a strategic decision.

Do you trust or betray? (Prisoner’s Dilemma)

Do you compete or coordinate? (Nash Equilibrium)

Do you consume or conserve? (Tragedy of the Commons)

Do you take the leap of faith or settle for safety? (Stag Hunt)

There is no single way to "win" life, just as there is no single way to win a game of chess. But by understanding these fundamental dilemmas, we can make better decisions, build stronger relationships, and design smarter systems.

Because, in the end, life isn’t about winning one game—it’s about playing the long game.

What game are you playing today?